My project And For The Rest is a photofeature and cover in the latest edition of Theatre Heute, accompanying an article on current politics and arts funding in Switzerland.

Stand Off

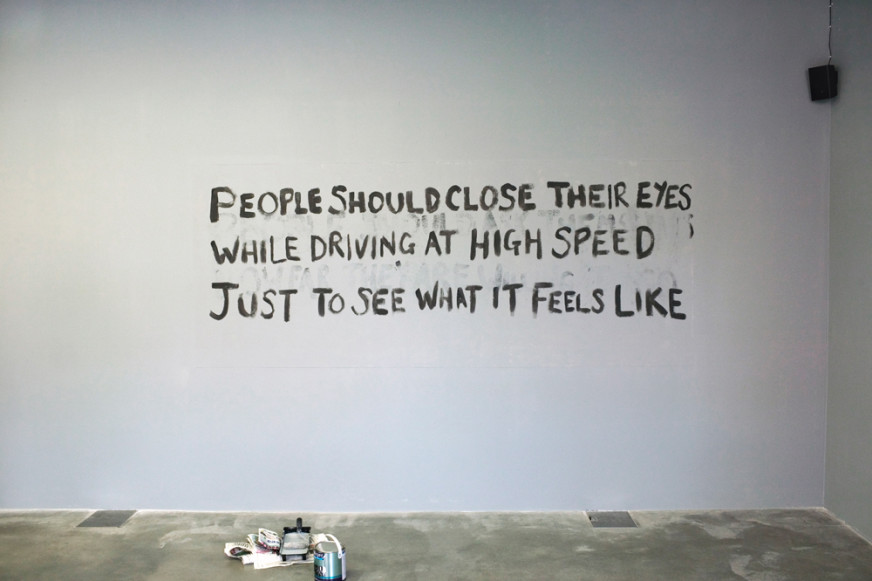

Some video of my sound piece Stand Off, in situ in my For Now solo exhibition at Plymouth Arts Centre. Runs until January 3, 2016.

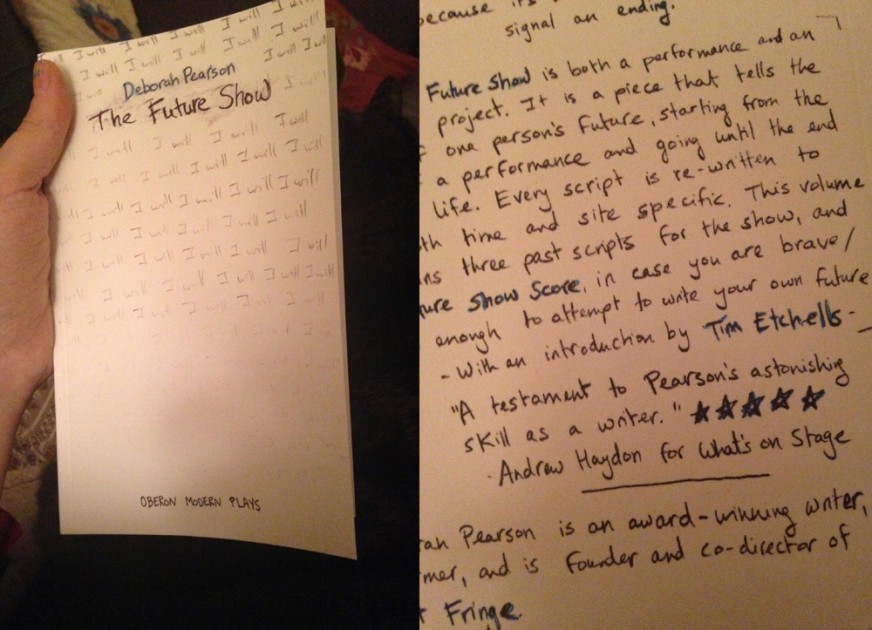

A Task Become A Theatre – Intro to Deborah Pearson’s The Future Show

Sharing Battersea Arts Centre this week with one of the most interesting performance-makers in London right now, Deborah Pearson, who plays a double bill of performances Time Pieces, comprising her solos Like You Were Before and The Future Show. The performances are at 7.15pm and 9pm and run until 7 Nov. Through the same week and into the next Forced Entertainment plays The Notebook, which runs 3 to 14 Nov, I’m also presenting my solo A Broadcast / Looping Pieces on Saturdays 7 and 14 Nov at 5pm.

I saw Deborah’s Future Show a couple of times now, once as part of the Irregular Evenings series Vlatka Horvat and I were curating in London, and later in this years’ Malta Festival Poznan which I co-curated. It’s a really great piece. In a timely fashion Oberon Books are just publishing a book of The Future Show, containing three versions of the text for the piece, which is rewritten for every presentation, along with Deborah’s extended notes on how to make your own version of the work. Deborah asked me to write the intro for the book, which we agreed I’d share here – it was a pleasure to engage with the work in some detail. You can order a copy of the book at Oberon’s site – it’s recommended.

***

A task become a theatre

It’s all there at the start. The woman at the table, the folder of A4 pages, the glass of water, the act of reading (a task, which here becomes a theatre).

In fact she starts already teetering, stepping off the edge of the moment she occupies and into the future, boldly in the first sentence already stepping to the end of the performance, to the closing of the book and the ocular cancellation of the text she is reading from, by that time completed, and in that same moment stepping to the ocular cancellation of your vision, the dimming of the lights, and stepping also to your predicted applause; the acoustic cancellation of the spell of her voice. She steps forwards into the future and keeps walking, ahead of us, reporting the future as if over-her-shoulder but in fact speaking directly to us, reporting what will come in good part as a set of non-negotiable facts, immanent facts, facts-to-be, of which her present self, whilst calling them back to us, makes little (or is it absolutely no) judgment, comment or assessment.

“And I will say…”

And in the next hour or so she will race ahead of us thus, talking up time, taking time and making it, making years of our minutes, soft, precise, pedantic in the detail of her conceptual life, its scenes and stages, its ups and downs through and in the jittering flow of which, she is slowly and softly painting herself into a corner.

It’s all there at the start. After the holiday, after the PHD is done, after the brief fling, after the shopping trip, the travel for work, after some moment of reflection, after this or that, the growing older, the love, the family, the work, after all of that, of course, she will reach that corner and die. It’s inexorable. She will die. Tonight. And again tomorrow, and, if business is good and the audience up for it, she will die again the night after, progressively more tangled in her own story versions and entrails, but always dying, always the same.

The presence of the book on the table, the accumulating versions of her future, three of which are included here, is testimony to the core status of the piece as language game. You feel a bit of Georges Perec here – with his endless descriptions of the same view from the same café windows, or his words wreathing always the same banal objects, as if by returning his gaze to these scenes and items repeatedly they might yield their truth, their real story. Perhaps Pearson takes this approach to her future – looking and looking again; refining it, working it down and around, mapping the flux of the possible towards the singularity that she will inevitably be, the her that is closing slowly around her.

But Perec’s endless return to the everyday makes no claims to reach for the unknown; it’s avowedly an act of looking, an insistence on what is – in equal parts tedious and joyous, finding the unseen rather than the unknown. Pearson’s text meanwhile steps away and out from the already evident, searching her own present, her own sense of herself, the narrative of her own life, for the seeds, signs and fissures that already lead, point and open to her future. Everything now, everything present, is only fuel to her future; the lobby of the theatre, the staff at the hotel reception, the taxi driver, the friend in the hotel, the clouds above the city here become openings we watch her push at gently, as she steps out future-wards. We watch her go.

“And I will take the District Line..”

Watching Pearson I have to think a little of the protagonist of Russell Hoban’s Pilgerman (1984), whose Young Death is following him through the novel, gaining shape and clarity with the passing of the years, getting clearer, sharper, better defined. Or of the Herman Hesse novel The Glass Bead Game (1943) in which acolytes or students of the game undertake to write three versions of their lives (and deaths). I’m thinking too of the performance I made with Forced Entertainment The World In Pictures (2006) which ends with performer Jerry Killick’s accelerated imagining of the audience as they leave the theatre, through the days and weeks in which they do or don’t remember what they have seen, leapfrogging years through the rest of their lives to their eventual deaths, to the deaths of all that know them, to the transformation and forgetting of languages, to the change, decay and then destruction of the city outside, to the end of human civilization, to the eventual erasure of the world, the place of the earth left vacant as only a vacuum in space. I’m thinking also of visual artist Beth Campbell’s My Potential Future Based on Present Circumstances (1999 – present) in which she has, over the course of many years made a series of diagrams and drawings in which her options, potentials and possibilities, play out in gardens of forking paths, flow charts that map her successes, relationships, depressions, discoveries, failures and forthcoming life-choices as a network of either/or’s, played through to multiple conclusions.

But Pearson’s work is its own universe, a methodical conceptual writing-project undertaken over a period of years, whose reflexive task involving the adjustment and ornamentation of sentences, paragraphs, linguistic images and futures is also a kind of magic act, a conjuring and transgression of quotidian time. Gentle though the piece is, undramatic even, its dynamic heart is meshed with deep cultural taboos concerning prediction, and the fearful properties frequently ascribed to the actions of speaking and writing when they address themselves to the future.

To write your future, to speak it, to name it, is an act invariably shrouded with unease. The act of prediction, of seeking knowledge ahead of time, of articulating or claiming knowledge in advance of events puts the subject above or outside the constraints in which humans are usually expected or burdened to operate. Premonition, prediction or pre-knowledge is a rupture in the temporal order, a reach for power, a transgression; an unseemly land-grab from the gods, fate, free-will or the random machinery of the universe depending on your worldview. “I will.. and then I will..” is a form of impossible knowledge, as forbidden as it might be desirable. The act of reading on which Pearson embarks, from the outset of her piece, however simple in its means, unassuming in its performance or cool in its conception and execution, is non-the-less a violent magical transgression, a breach in the quotidian universe.

Those who author or are party to such breaches in the temporal banal, demanding, claiming or proclaiming impossible knowledge, are doubly trapped by their actions – the future they name may come to pass (the past utterance become a future prison), or, on the other hand, the future as named may not come to pass, its path failing, swerving, changing or mutating in new directions, reacting to the predictive utterance, avoiding it, or obeying but at the same time thwarting it. Narrative, for the most part, is far from kind to those who know, claim to know or seek to know the future.

The loosely programmatic nature of Pearson’s project – moving forwards day by day, through weeks, months, years of her life – is a simple but audacious piece of temporal trouble-making and we feel the self-destructive charge (and burden) of it, quite regardless of any sort-term playfulness, poetry and self-invention that the piece typically supplies. We worry for her, knowing that she reveals (and will end) herself, suspecting (with however much irony) that the choices she makes for the ‘Deborah Pearson’ described on this particular night may have consequences for the Deborah Pearson who sits before us, down the line. She is (to put it bluntly) tempting fate, and whilst she is kind (or selective) to herself on the whole, ones concern is not so much that her alleged future will come true, but rather with the tangle of accumulating possible ironies, possible coincidences, possible twists and turns that she is making a ground for, up there on the stage, throwing her linguistic mirror-selves into the universe and watching them cloud, crowd, fail and fall around her.

She is kind to herself. Pearson’s predictions offer little or nothing in the way of drama or hyperbolic invention; no car crashes, no revolutions, no murders, no court cases, no hauntings, no divorces, no rapes, no debilitating or disfiguring illnesses, no grinding poverty, no war or social collapse – just a micro-managed continuous everyday of her life, her ongoing life, pretty much as lived at the point of her writing but continuing, changing. She takes her task playfully, seriously, with love, making a miniature, with all the care, attention to detail and engagement that might suggest. For all that the performance is a highly manipulative, affective architectural construct there is nothing brash or trash here. Instead you sense her taking care with the materials. She takes care of the life she is describing, lest the game of the piece collapse to the status of a mere word game, tending the construct of her futures-described as one might expect her to take care of her own future proper.

Her care takes other forms too. In the text she skirts her own death, at least in the sense that she never names it exactly as such. She plants children in her future but again, avoids the full on fate-tempting procedure of naming and numbering. Her work remains hazy. She appears vague as to the fate of her husband. Throughout there are details, fragments of future. But despite its apparent straightforwardness it remains somehow only the shape of a life, an outline, with clear views only at certain moments, hologram fragments which gently imply the larger scene, the unfolding passage of weeks, months and years. She goes forward.

“And I will reach up…”

There is a large sleight of hand of course, in Pearson’s presentation of The Future Show as a kind of experimental time-lapse theatrical selfie. She is, for the most part, busy telling us that it’s all about her, that this is yet more millennial self-obsessive diary stuff. But it’s not, not really, not like that.

The reality of this task become a theatre, is that it’s an act of reading in its other sense too; that of reading the future, each syllable of the performance functioning as a sign, oracle and prediction, her letters, marks on those printed pages in the binder on the table, as much tea-leaves as alphabet. And of course, the quick of it is that throughout she is speeding our time just as much as she is speeding her own, putting our lives on fast forward, creating a space in which we reflect on our own futures, possibilities, the landscape of our own what’s to come, all the time slowly and quickly taking us to our graves, en route to her own.

We too will die. There are no straight or easy deals when it comes to forbidden knowledge of the future – only crooked ones, only deals in which the client gets burned. Whilst as spectators here we never asked that our fortunes be told, we should have known very well that the mirror would turn, kindly at first, but then of course not so benign, that we’d meet our ends in following to hers.

Even before we see her end we are also moving to ours, stood since the very beginning on a precipice, our years talked out and away as seconds, our lives slipping past in the same hyper-speed, stop-motion as hers, locked together as we are, like objects falling in orbit of each other.

Enjoy. And take care.

Tim Etchells.

#Dibber (unpublished fiction, a short tale from Endland, 2015)

#Dibber

Dibber got a letter from Celebutards demanding him for Induction next Thursday or face big problems with Benefits large and small. After customary complaints, idle moaning and/or delayed commiserations from immediate family, he got his conscripted ass down there early – sitting in the waiting lounge with polystyrene ceiling muzak, litter of aged magazines and a flat-screen receptionist for 48 hours, tuning to the strange comings and insidious goings of the building, the specific creak and crackle of its cctv, pesticide, aircon and the buzz, clunk clatter of the Pepsi Machine, Juicer and alleged water cooler.

When it came to induction the advisor bloke sat him down in the windowless cubicle, offered pain killers and Detox Cigarettes then ran thru the spiel – everything was embargoed, nothing they said could go out of the room. The plan was a year long conscription, with option on two further years, dependant on ratings, socials and a whole lot of other stuff like pre-recognitions, cross-sells and co-convergence that a straight A’s idiot like Dibber couldn’t claim to understand. They took his fingerprints, appointed him a designated Driver, outlined a programme of corrective dental work, filled his face full of Botox, ringed his flabby arms with a Celtic looking tattoo, sprayed him with OrangeTan, did something weird to his hair and sketched out the next six months in partial detail while the wardrobe people took his measurements with a laser-device. Later they took him down to Administration, converted his name to a hashtag, signed the papers and let the wagons roll. #Dibber was cast as a Drunken Oaf type with something of a Prince Charming thing, a well-meaning caricature whose looks would slowly melt butter but whose mouth would quickly shoot blanks. They had him down for a romance with Helena Bellend, then a bust-up that would hopefully rock Twittersphere, he’d get in a punchup with Mario Mixface, apologise, flare up on PintRest and apologise again repeatedly then shack up with a new older celebutard called Martha Martha that they were launching the same time as #Dibber. The idea was to cross-fertilise followings, routing trickle down audience from Bellend and Mixface to launch the new stablemates, and at the same time add spice to the existing properties who were losing their peak in some key market segments. #Dibber was pretty much lost at the first plot twist, his boner for Bellend quickly diminished by the prospect of later enforced carnal endorsement with Martha, whose haggard Real Face was only partly hidden by the layers of make-up and pioneering surgery already enacted upon it at Celebutards clinic. Some of the surgeons there were practically cubists – hardcore ex-military nut jobs straight out of Texas, Iraq and Afghanistan and working at the absolute ethical cutting edge of what could be reconstituted using a human face after carbomb injuries.

#Dibber got through the year OK, appearing in public here, there and absolutely anywhere, always surrounded by paps, prats and photodrones, rolling deep and loud with a gang/gaggle of other celebutards of variant types and persuasions; it was 365 of 24/7, opening Night Supermarkets, clutching swag, closing down Hookah Bars, singing at a Charity Gala for Refugees from America, brawling in Shoreditch and Dolphin Square, breaking up with Bellend after a viral fight in Frank Bruno’s Restaurant, then licking his wounds and the aging surgically-restored pussy of Martha in a sex tape that absolutely no one wanted to pay for but everyone wanted to see. At the end of all the rollercoaster he was addicted and exhausted, a recognisable face and certainly a brand of some kind, but the writers at Celebutard had no further use for him and they dumped him back, without warning or therapy, into Unscripted Reality, just a handful of catch phrases left to his name.

Down there, in the lower depths, ‘on the other side’ as they called it almost euphemistically, he met a few other former also-rans, blurred forgotten shapes clinging on at the edges of the scene like Candy and Molotic, then moved to Margate and then later to Hastings, got a job as a DJ in a defrocked revamped hotel disco, doing short slots on the decks at alternate weekends and running drinking games with the crowds at consecutive midnights, maintaining the drains, the foam machine and the smoke machines in his spare time. His eyes, if you looked in them were dead. He was just a shameful echo of himself he said, technically alive but in any commercial sense a wreck-job, some fucked brand, a Woolworth’s, beyond reinvention.

Three or four years he lived that way, no one was counting. #Dibber tried – he kicked the drugs they’d addicted him to, got back together with his previous wife from his previous life, had a kid with one of the girls that worked the candid lightshow in the hotel disco. He got fatter, sadder. Made up with his parents but nobody cared. #Dibber lay fallow. He kept the hashtag but wouldn’t even glance at it. He stayed out of Old Bill Londons, stayed out of The Arm Bar and stayed out of NonDom Pete’s. He wouldn’t show anyone the hologram of him punching Mixface anymore, he wouldn’t talk up his latterday social stats, wouldn’t even mouth the words to his best known catchphrase if it came up anywhere. At night he missed the sound of the photodrones and in the morning after the night before, he missed the ritual reconstruction and routine re-assembly of his drink-erased antics spread out all over instagram and vine.

The years passed. Texas came back on-grid. Putin was inevitably executed. The pubs offered nightly re-enactment of Cameron’s pig fucking youth. Even ISIS mellowed a bit, became a bit more chill. Things changed. And in a way nothing changed.

And with the turning of the earth, after an indecent interval, someone from another Channel (probly more edgy, really more now) came down the club and sought out small chat with #Dibber as he cleaned behind the bar. #Dibber said yes of course and before he knew it he was signed sealed and indentured to some weird comeback show in which a shitload of former reality stars were being flown up as payload to an almost derelict Russian space station (SkyLub) to see how long they’d survive. If #Dibber had had a qualified lawyer or a competent agent or a semi-supportive family member, friend or even casual acquaintance of no fixed gender or abode they would have advised him strongly not to take the gig, but he had no such thing in any such category and he accepted it, with open arms. A route back. Another beginning.

The training camp section of the new SkyLub scripted reality won awards in Macau and Ukraine. #Dibber was a hit within a certain demographic. He had good timing for gifs, decent body contact, fair presence, a lot of it convergent. He had catchphrases too, a few of the old ones were worth something still and he soon had new ones from the Anti-Gravity episode and a kind of joke contest skit/spat with Karen Splita. The episode on the day before the Launchpad Special, where he was reunited with Bellend (almost unrecognisable under the layers of her new surgery and non-prescription animal tranquilisers) got good ratings. His perilous space walk in a largely exaggerated meteor storm was an absolute sensation.

Things looked good for a #Dibber revival on his return to Earth but either the physics or the focus groups, or the wonky pre-fall-of-the-Soviet-Union-space-tech took their own routes towards closure, no one could be sure. Some people said that most likely the reality writers just decided to cut their losses and go for broke and instant ratings, bringing on a slow leak out of the oxygen of publicity and a final crash to earth for the wreckage of the burning SkyLub. There would be no survivors, the scripters and the mission tech were all agreed on that much at least.

Reviewing his best bits before the inevitable burn up demise #Dibber was filmed in the long abandoned gym of the space station, trying to do sit ups in Zero G, ending up flipping and flopping all over the capsule and laughing. For a moment, even with the low-res footage and the sound-sync issues, you could almost see why he was celebutard material in the first place, his boyish grin and general genial humour, the ghost of his physique still speaking somehow through his flab. It was quite moving when the different doomed crew members went one by one into the command cabin or whatever to tell their last words before the re-entry that would fireball the fuck out of the ship and kill them all. Gonad sang a song that his brother had taught him, Shirl, Shack and Shakey kissed and made up, Veronica Toothache dissed the bitches back home, Randy did some kind of whacked out Michael Jackson tribute that was a bit miss-judged and the ratings didn’t really endorse it, Abbi flashed her massive and massively predictable cleavage, Raj made a speech about mental illness cos her dad was a mentally ill and she wanted proceeds and donations to a charity. Anyway. When it came to #Dibber he had in mind to do a kind of medley of his catchphrases, set to a melody he’d been working on using a acoustic guitar left behind in the galley by one of the former Russian crewmembers back in 80-whatever, but in the end he just sat there alone in the cabin with the guitar and stared at the camera, all quiet, saying nothing, hardly moving in the softly blinking lights. He wondered how long the techs or editors would give him there, with just this silence and his stillness, and if the socials would say it was poignant or just sad or pathetic or selfish or just way too deep or like weird or whatever. Come what may. He held it as long as he could and later went back in his bunk at the crew quarters, eyes tearing up.

Three days later the SkyLub burned up on atmosphere in a quick burst of star fire, a few lumps of which inevitably came crashing down onto earth in the desert somewhere, down West, near where Los Angeles used to be. #Dibber’s silence went viral for a while as #Dibber, #DibberSilence and even #TheSilence. There was something about it, no one could quite say what it was, but people were fascinated, gripped, a little bit haunted even. A kid in Cairo put a soundtrack to it. Someone else dubbed poetry subtitles. A kid in Brighton, Endland (sic), sang an old sad and kind of eerie song. If you watched that, and could concentrate for a minute or two, however long they let it run, it could almost make you cry.

Some Imperatives – EXPERIMENTICA 15

* EXPERIMENTICA 15

4 – 8 November, Chapter, Cardiff.

This festival of live art, performance and interdisciplinary projects features Etchells’ performative installation Some Imperatives, across the 5 days.

War in Words 1: Dialogue with Lara Pawson

In 2014, Kaaitheater in Brussels ran a season titled Up In Arms, which featured a range of projects by artists responding to questions of international conflict and the legacy of World War One. They invited me to do a series of dialogues or correspondences with artists involved in the season, the results of which were published in Kaai’s quarterly bulletins. I’m posting those dialogues here in the Notebook, just to give them a different profile. The first correspondence, below, is with the journalist and writer Lara Pawson, the others are with Pieter De Beuysser, Vlatka Horvat and Pieter Van den Bosch.

Image above: Vlatka Horvat from her Up In Arms series

***

Dear Lara,

In the text you wrote for the sound installation Non Correspondence you recalled your time as a radio correspondent reporting from Angola during its civil war. In your description important, weighty and dramatic scenes – great violence and suffering, fear and trauma – are often placed next to many kinds of banality, everyday actions and incidents. In our conversations it has seemed to me that one of your impulses in the writing was effectively to humanise war – to deal in some way with its ordinariness and its banality, or to stress the persistence of the everyday (boredom, trivia, laughter, sexual desire) even in the fearful environment of war. In your text the image of a soldier who has shot off his head, his body slumped motionless on the stump of a tree, circulates in the same act of remembering as the image of a bunny rabbit being looked after by a bunch of guys that run a bar, or your description of searching for tampons or good coffee during the conflict. At the same time your descriptions of ‘peace time’ or life away from conflict – drawn from your childhood and later life in the UK – are often shot through with intimations of violence and everyday tensions around identity, gender, race and politics. It is as if you want to point to the peace in war, and the war in peace, and I am wondering if you see yourself as countering the common media description of wartime as something ‘outside’ of the human, distinct from the everyday; something purely awful and inexplicable.

What is it about that media description of wars that seems wrong to you and what interests do you think it serves to maintain? Do you think there’s a political dimension to the media insistence on the time of war as time of pure conflict, devoid of all other qualities or experiences?

All the best,

Tx

*

Hi Tim. Yes, I do seek to counter the common media description of war but I really couldn’t have written a text without the persistence of the everyday, because that is precisely my experience of war, or conflict. It is the everyday.

We can’t ignore the fact that we are both writing in London, in the UK. Although we have had conflict here – the so-called Northern Ireland conflict – many of us have never experienced war. Yet we hear about wars all the time, sometimes conducted in our name, sometimes far off and apparently “foreign”. The raw effects of war are largely absent from our lives. We don’t have to run from shelling; we don’t have to confront soldiers with RPGs on their shoulders when we drive two miles from home, etc. When I came back from Angola, what really frustrated me here was the widely held view that war is not something “we” do. People would ask me about what I’d witnessed in Angola as if it was another universe, a place with aliens that had nothing in common with our life here. And yet, what I had learned there was how fragile life is and how fragile we are, and how little it takes to reduce a society to rubble, both physically and mentally. Until you’ve actually seen a city blown apart by bombs, it’s quite hard to imagine how it happens. But once you’ve experienced it, there’s no going back. The line between apparent peace and apparent war is very very thin. We are all living on the precipice.

To come to your question, I think there is a gap between how war is presented, particularly in mass media, and how war really is. That’s not to say that when you see images of, say, Gaza being bombed, it is not real. Of course it is. But – perhaps because of the screen or the paper at which we gaze – it seems far away and so other. Due to the restrictive structures of 24-hour news, journalists are under immense pressure to show the extremities of war: the blood-stained dead children and broken buildings. All of this is real, I’m not denying that, but we rarely see images of the shops that continue to sell, of the man who continues to buy condoms, the woman who still argues with her sister while making mint tea or rubbing moisturiser into her skin.

In most journalism, restrictions on time and pressures to be fast push reporters to seek shocking scenes to hold their audiences’ attention. In doing so, they omit the other things that are also happening – the everyday – creating an idea of a place that is partially truthful and partially false. There is a political dimension to this. In part, it’s often – from the position of being in London or Western Europe – a desire to reproduce the idea of the so-called civilised “we”, up here, in our clean and tidy former empires, gazing at the chaotic “them”, down there, in their messy, confused, out-of-control state. It feeds our political arrogance as well as our foolish superiority complexes of being humanitarian. Importantly, the media coverage that most people consume also feeds the idea that those wars out there are not part of our lives and that we are not complicit. Of course, we are.

Lara

*

Hi L,

Thanks so much for what you write. I also wanted to engage with you about remembering and forgetting. In Agota Kristof’s The Notebook, which I’ve just worked on with Forced Entertainment to adapt for the stage, the protagonists witness the passage of a ‘human herd’ of two or three hundred civilians being marched at gunpoint on foot through the town in which they live. Clearly troubled by what they have seen, the protagonists are told by another character:

“You’re too sensitive. The best thing you can do is to forget what you’ve seen.”

The two boys who narrate the story, perhaps inevitably, insist in response, that they “never forget anything”.

This rang a bell for me, as I remembered that when you started work on your Non Correspondence text, you wrote to me in an email:

“The funny thing is, even though I left the Angolan war 12 years ago, I still find it so hard to get it out of me. It’s there forever and feels alive inside me. I think that’s partly a kind of quasi PTSD and something to do with memory.”

I am wondering if you see the vivid persistence of these memories as an unwelcome thing – as something that you would like to rid yourself of? Might forgetting be preferable, or even healthier, than remembering in this instance?

Best,

Tx

*

Tim, I love these two questions. My immediate answer is a loud “No!” Forgetting would not be preferable. In fact I often wonder why I was the lucky one, to get to go to live in Angola in the summer of 1998 until Christmas 2000. That experience has given me such insights into the world in which we live and into human nature. Given how much war there is, all the time, in so many places, I’m glad to be able to understand to some extent what people are going through. However, I can’t answer this honestly without also admitting that I became profoundly depressed about the Angolan war and the conflict in Ivory Coast too. Those memories drove me to a very dark place. There were times when I feared I’d never get out, that I’d never be able to be happy. So I don’t want to trivialise the memories because, for a while, they paralysed me. The funny thing is that now, the happy person that I am, I worry about losing those memories of war. If they vanish what will I do? I don’t want to lose that vital understanding. Will I have to go to another war? Or will war have come to me, here, by then? Consider climate change, population growth, apparently unstoppable levels of greed and super-capitalism, it seems to me to be inevitable. Maybe I’ve been reading too much JG Ballard. Or maybe there’s a part of me that wants that to happen.

L

*

Lara,

Thanks again. Finally, linked to the question of remembering, I’m thinking a lot about what we are doing as artists and writers in returning to (or thinking about) the site of war and conflict. Benjamin writes that ‘”The storyteller has borrowed his authority from death” and in doing so perhaps acknowledges that there’s perhaps something parasitic in the relation between art and trauma, even if (crudely speaking) the art is supposedly reflecting on, teaching about, seeking to understand and prevent repetition.. Does it even matter, this act of returning? And does it matter that we conduct this return and consideration of conflict in our role as artists and writers, and not only as historians and journalists? What do you think art in particular can bring to the table that some other, supposedly more objective, ways of responding to conflict might not do?

It’s a beautiful sunny day in London and these are all big questions that I am shooting to you today I know. I look forward to hearing from you.

Tx

*

Well, Tim, I don’t really believe in the possibility of objectivity. Although we journalists and historians may present ourselves as objective narrators, it is nonsense. We’re as partisan and emotional as anyone else. I think the advantage artists have over academics and journalists is that they don’t need to pretend to be objective. People expect an artist to be emotional and subjective, and in terms of responding to war, this allows an important and extraordinary freedom. However, I worry a lot – perhaps unfairly – about artists and writers reflecting on war without having experienced it. I get quite uptight about this. I worry that there is an exoticisation or a romanticisation of war. Could this be the element of the parasitic that you are referring to? I worry about my own parasitic relationship to Angola’s war. Recently, an elderly Angolan man and his Dutch wife spent a weekend with me and my partner. The old man wanted to talk about my work, specifically about my book about a covered-up massacre in Angola in the 1970s. At one stage, he became quite cross with writers – he named white Angolan and Portuguese writers, but I am sure he was including me – who, he said, become famous by spinning Angolan tales. These writers would be nothing without Angola and its war, he said. This old man had fought in the liberation struggle: he had put his body on the line for independence. I felt a lot of empathy for him, yet I also know that artists and writers can do so much to enable us all to think more deeply.

My own fascination has long been with Samuel Beckett’s work, much of which is a response to WWII and the Cold War. He has helped me make sense of my experiences in Angola in a way that no history book could ever hope to. Likewise, recently, I came across the work of artist, Marcelle Hanselaar, who grew up hearing her parents talking about WWII and Germany’s occupation of Holland. Today, she cares deeply about wars taking place around the world. Her paintings are dark and violent and people have told her that they couldn’t possibly live alongside her work. I find this intriguing. We live alongside so much awfulness and are complicit in so much violence carried out in our names by our states. How could anyone be afraid of a painting? Is this a sign of people’s desire to hide from the realities of the world? I find this hard to understand, because my own quest is always to be rammed up against the dark and the misery and to stare it in the face. I would love to live with Marcelle’s work because I would be reminded of the fragility of our apparently peaceful lives here. I would be reminded of my obligations.

I suppose what I am saying is a bit of a cliché: the idea that, unlike journalism or academic texts, art can hit us in our hearts without us fully understanding how. It is an organic, fuzzy process. While watching The Notebook I was fighting back tears. I didn’t know why. The last time I felt like that was standing before Anselm Kiefer’s huge textured oil paintings of fields of sunflowers. It was in Paris. I had to leave the gallery. I thought I’d explode. Now that doesn’t happen when you watch the news. Not to me, anyway.

One last thing! I don’t think that art, or journalism, can prevent war. We can’t control that. But we can keep on trying to remind ourselves of our frailty and of that very very thin line between apparent peace and war. That matters a lot. We must stop ourselves from becoming arrogant. We must try to crack that.

You wrote that it’s a beautiful sunny day in London and I agree. It is! It is! And this heat reminds me of Luanda. What heat. Thank you.

Lara

War in Words 2: Dialogue with Pieter De Buysser

In 2014, Kaaitheater in Brussels ran a season titled Up In Arms, which featured a range of projects by artists responding to questions of international conflict and the legacy of World War One. They invited me to do a series of dialogues or correspondences with artists involved in the season, the results of which were published in Kaai’s quarterly bulletins. I’m posting those dialogues here in the Notebook, just to give them a different profile. The second correspondence, below, is with the Flemish theatre maker and performer Pieter De Beuysser, the others are with Lara Pawson, Vlatka Horvat and Pieter Van den Bosch.

Image above: Vlatka Horvat from her Up In Arms series

***

Dear Pieter,

In London I watched your performance Landscape with Skiproads, presented during a LIFT event exploring the legacy of the First World War. The show stayed with me so strongly; an extraordinary work.

So far as I can remember though, and this isn’t a complaint (!), there were no concrete references to the ‘Great War’ in the performance, which comprised a long narrative connecting a set of ordinary and at the same time unlikely objects displayed on the stage. Each object had an elaborate history narrated through the show, and as watchers we soon learned to anticipate that even the most banal of them would, through the narration, prove to have a spectacular connection to events and ideas of great significance in the 20th century and beyond. The nondescript glove on a plinth, for example, turned out to have once belonged to Adam Smith, the advocate and architect of Free Market economics, who, in 1759, famously coined the concept of the ‘invisible hand’ of the market – a metaphor for the forces, which he said, allowed capitalism to self-regulate. An ordinary bell meanwhile, displayed elsewhere onstage, was revealed though your narration to be the very bell used by Pavlov in his iconic behaviour and conditioning experiments in St Petersburg at the start of the 20th century.

I wanted to ask you, in this context, about dealing with history in your work. There seems to be no fear on your part, neither in picking up these concrete signs and symbols from the past, nor in inserting them into a narrative framework which runs free with them, whilst at the same time ‘making use of’ their significance – incorporating them into a schema and argument very much of your own. What’s your approach to history in this and other works? What kind or kinds of responsibility are you negotiating when you work with these materials?

And, on a slightly different topic, despite its lack of direct reference to the First World War, do you think that this work has some relevance to the way we might think about it? How might those questions of responsibility change in relation to institutionalised carnage of that kind?

Behind (or through) the detail here I think you see me scratching at some larger questions. What does it mean for a work to take on these matters of historical import? Many works claim to be about particular topics (usually an important one) but in fact they can’t get near to what they claim to research or present. I didn’t have that same impression of falling short with your work though. I was very interested in the way you seized those alleged artefacts, those signs of big ideas, and then worked them against each other to make something else. It seemed to me you made something ‘bigger’ than the sum of the materials. So often, when people grab content of significance it’s the other way round – the content is big but the work stays small. These aren’t precise terms of course! It’s Sunday and I’ve been writing all day. Perhaps I’m trying to think about work that concerns itself with ideas, and not so much with facts. Recounting facts has its place of course. But watching your work I got the sense that we need more than facts if we are going to make sense of what has happened to us, and where we are going. We need a poetics. What do you think?

All the best,

Tim

*

Dear Tim,

Thanks a lot for your letter. It is true, Skiproads doesn’t deal literally with WW1. I could have inserted some concrete references, but that would have been merely anecdotal. While we drown in anecdotes, we have no story. That is the more fundamental issue. It is valuable that we remember what happened in WW1, and I assume we just have to take for granted all the touristic / opportunistic projects that pop up in this process. But a commemoration should be a rethinking and thinking is a forward-looking gesture, a movement. In fact, one thought that drove me while making Skiproads was the idea that an overload of history can be very damaging for public health. It’s common sense that a shortage of history might lead to recurring stupidity, but at the same time, an excess of history can lead to it crumbling under its own weight; an overload of history threatens to paralyse the present, to crush forward-looking vitality.

Our era already has an inclination towards what has been, rather than towards the potential of being, and when we turn to commemorating WW1, it seems more crucial to address this question of history itself, than it might be to celebrate yet another brave war nurse. Nowadays, Europe is a museum; collecting, protecting and scraping a living from the cultural, moral and financial wealth of what was, cherishing and living off the legacy of our grandfathers. We have been turned into a moribund geriatric posterity preservation scheme. Sloterdijk said: “The 21st century will be the century of the subject” – well, let it come! ‘Cause for now it’s still mainly the century of the elder, wandering spectator having reached a mood in which the idea of a new beginning is no more then a beautiful, melancholic idea. In order to effectively resist this historical condition, I think we need history to be the power fuel, the shaping power of the contemporary. Skiproads tries to contribute to that process and consequently I collected some objects that were present at key historical moments; the moments when we became who we are. In real. Or at least as real as possible. In the facts. Or at least as close to them as possible.

The political calamities that we live today in Europe find their origin in these objects and I wanted to invent a new configuration for them. I use them, with a kind naked naïveté, to sketch something better with them. For me the performance begins as a sort of a historical mine-clearing operation; a way to make room for a new landscape, that leaves the deadly beaten tracks aside. It’s an attempt to rise up from our history. The old landmines that haunt our present-day human and political conditions are on stage, exposed in the here and now, where all of us can grab, touch and rearrange them. Every night I hope that the performance can remind us that it is possible to have a grip on the things that make our history. Of course I know this is a big ambition, but at least the objects are on stage and hopefully, we, the coming subjects of the 21st century, can get some sense of the graspable, and thus transformable history we live in.

Your question about the kind of responsibility we have in dealing with these materials is a crucial one. You write, “maybe we need more than facts.” I completely agree – we need a poetics. But it should be a poetics that remains true to the facts. After all, one can remain true to reality in the most wild, magic and imaginative stories just as one can tell the most realistic naturalistic stories that are completely escapist entertainment.

I think that’s the decisive factor in the ethics of these aesthetics; having respect for the facts, and a dedicated love for the real. As you certainly know, there are “merchants of doubt”: lobbyists that alter or simply hide scientific facts in order to increase the profit of the companies or politicians they work for. They transform facts through fiction, using much the same method as artists, but doing very dirty tricks with it. For instance, scientific results on climate change are structurally transformed by lobbyists of petroleum companies and by the American Republican Party. If, as citizens, we don’t have access to facts, to correct facts, then we can’t legitimately make our choices or cast our votes, and without that our entire democratic system collapses. Fictionalising facts is a dangerous method we need to be careful with; threatening to undermine the basic trust our democracies need. Maybe the danger of this method – transforming facts with fiction – reveals its power? But what should the parameters of such a poetics be? I’m curious to hear your thoughts on this.

When a performance is good, I believe, it is a smuggling route between fiction and reality. The better it is, the smoother the smuggling goes. It should work well into both directions: remaking reality through fiction, and when it’s really great, enabling people to alter the material relations they’re living in, and when it’s fantastic it might even help people reclaim an existential viability. In this coming and going on the smuggling route between fiction and reality, a mysterious event might take place that some call “beauty” – I don’t even know what it is, but I do know that when it happens it is a simple enigma that endlessly calls out.

I have a strong feeling that one of the key questions in today’s performance and theatre is this relation to the real. I’ve seen so many performances struggling with it – some perversely using the real for just a spectacular emotional effect and others remaking it in a truly transformative way.

Warm greetings,

Pieter

*

Hi Pieter

I really like this idea of art as a space in which to reclaim history as something with trajectory, movement, thought and change, directed towards the future. There’s a spirit in what you write that I like too, just as I felt after the performance, when those familiar objects / ideas were buzzing around in my head in new ways that I couldn’t easily put back into words.

I think that precise difficulty – bringing the work back into a descriptive discourse – might be one key to what we’re talking about. It’s as if my ambition might be for an art that does not repeat or reiterate other kinds of understanding, but rather produces its own sense and discourse.

At the same time, I think you’re right about the importance of this question about art’s relation to the real. I think we’re feeling that in a new way, not in the old artistic staple of ‘is it true or is it illusion,’ but in the profound sense we have now that fiction and fact are braided around and through each other so very deeply. The understanding that our contact with media, or with fiction, writes deeply into our experiences and perceptions of realities; that our accounts of the truth are always, in a sense, fictions; that ‘reality’ is not what it used to be – these are almost commonplace positions of popular culture. But knowing that, and living it on a daily basis, we still have to proceed. That’s where the poetics comes in, and with it your question about the parameters of our relation to fiction in fact, and fact in fiction.

You point out that not only artists are busy subverting and rewriting stories; all those lobbyists, Transnational Corporations and politicians are very busy with it too. You see something similar in some of the hoopla of the WW1 Centenary. The loosening of the game rules attracts all kinds of players, some far from welcome or desirable. To me, what those guys are doing – in the spreading of misinformation around climate change, immigration, health or poverty for example, is trickery of the worst kind; I’d be keen to see them go to prison for their deceptions. At best, what artists do when they mess with the facts of historical and other realities, is something else. In Skiproads you made a constellation of materials that have a tension between them. The tension is connected to the significance of the materials and enhanced by the fictional materials you’re threading through those historical fragments. The tension in that constellation is not resolvable or reducible to an argument and that’s what confronts us and draws us in, leaving the piece to sit there as a powerful problem. It’s also what makes the work, despite its playfulness, still respectful of the truths you’re dealing with. Whatever else the work does, it lets those truths be – in their complexity, strangeness, inexplicability and irreconcilability.

I wanted to change the subject a bit though, before signing off. As well as this question of the real and the fictional, I am thinking about the dynamics between what can be seen and what not. I’ve been thinking about the streams of violent images generated by conflict that fly around on social media – the bloody corpses of children, weeping mothers and dazed hospitalised fighters from Syria, Gaza and elsewhere, all posted online by people keen, no doubt, to advertise the truth of what was happening. More recently we had the spate of ISIS beheading videos that are all over the internet too. I’m not conflating motives or situations, just pointing at these very different attempts to spread images of hideous violence in public space. There’s an urgency to these attempts to have us see what is happening; seeing is meant to cut through the walls we build to divide us from trauma, to shock us into action or understanding. But I am not sure I can really see anything anymore, not in that sense; I’m thinking about what it means to see things, and about the politics of what’s made visible and how.

Tx

*

Dear Tim,

How to see?

We are supposed to see the brutal facts of Syria, Isis and the rest, because we need to know. Democracy, human solidarity asks us to know – we can’t close our eyes. At least, that ’s the line of so many brave, important journalists. But you’re right to point out there’s something rotten in the land of naked truth. We’ve reached a level of access to pictures that one simply can’t bear it anymore. Where has this discharge of images come from? How did it come so far? Of course I do think I should know and see, but does seeing more of these images prevent terrible things from happening, or even help me to better understand them? I think we put too much false faith in confronting ourselves with real facts and real images, without thinking if our doing so makes any difference.

Now, I can imagine that if I were in a terrible conflict situation, I wouldn’t care about the subtleties; I’d just want the world to see what was happening. But this doesn’t undermine our question: we’re smashed to blindness with these images of hideous violence. Where does this tendency come from and where will it take us? What do these journalists, bloggers and social media users believe, or hope for? Sometimes I think they believe so fervently in the power of “real images” that they imagine the holocaust could not have happened if the internet had existed back then. Just imagine – the villagers of Auschwitz would be sharing images on Facebook, journalists would send pictures of the smoke from the chimneys – all as it happened. There’d be no traumatised Jews thanks to these pictures that would have enlightened the Europeans and “shocked them into action,” no Israelis eaten up with fear, no Palestinian occupation…

But I’m afraid that although we now see the most gruesome pictures from Syria and elsewhere, things just go on and on and nothing really happens, just like the genocide in Rwanda went on even as we were looking at it. So I’m afraid there is a dreamlike naïveté at work in this sharing of pictures of the real; despite the truth of the images, and the hopeful, communicative act of their distribution, they are soon dragged into a true blood-show that strangely disconnects us from the facts.

I think a historical shift has happened. Where once we put our hopes in systems of belief – myths and religions – now we seem to put all our hopes and expectation into this confrontation with naked facts. We expect so much from these images of the real. We have a surreal hunger for them, and for the reality they stand for. And somehow I think that alienates us even more from reality itself.

Now, I don’t necessarily want Jesus Christ to get involved in this, let him rest in peace, but his partner in crime, St Thomas, is still haunting our thinking. The apostle Thomas doubted the resurrection of Jesus, and wanted to see real pictures. He wanted to see the wound of Christ: only seeing is believing, only material facts and evidence are convincing. That story gave us much more then some magnificent paintings in which St Thomas is pictured with his finger sticking between Jesus’ fleshy ribs. It also gave us the primary force, or perhaps the genesis-myth of journalists and scientists; ‘we need to know the bloody facts;’ ‘Don’t fool with me.’ But I feel, in many ways, it might well be time to be sceptical about this predominant scepticism as well.

There is no reason to go back to the believing-rather-then-seeing business of Jesus Christ. But the scepticism that says you have to see this, you have to watch this, otherwise you are not informed and you can’t be a responsible citizen, is simply getting out of hand. Not only because, as you described, the so-called public space of media is just pseudo-public, but here we are back where we began our conversation: we need a poetics.

Myths, or fictions if you wish, can create a narrative out of a history that can’t yet be told. They offer an unfounded, groundless moment, which is perhaps the only ground from which a genuinely great transition towards something else can emerge. The bombs we see exploding on our screens are splintering us more and more every day. I hope that the poetics I’m looking for, using invented narrative alongside the facts that make us who we are, might work like an ark made out of all those splinters. It’s a dodgy boat, and it has many, many (wiki)leaks, but it might get us to make a passage, as fleeting as a night in the theatre. We are shaped by fictions as much as by facts, and very often, though we can’t change the facts directly, we can change the fiction that makes us. Perhaps that’s the only form of freedom we are capable of.

A last thought. In theatres of the former centuries, the performance started with unveiling the stage, pulling up and away the curtain. The gesture of pulling away the curtain, to unveil, to unmask… that’s the ultimate gesture of a bringer of truth; it is such a complex and beautifully loaded “first act.” It says: You couldn’t see until now; this is the moment you will see. That’s the same promise the Facebookers and bloggers with their shocking images and naked facts make. But in the old theatres, back then, only a fiction started with the raising of the curtain, and now, in our media, the gesture of unveiling leads to showing the most horrific facts, only the facts. I think we need to create something new out of both of these things, something that dances between them. Perhaps it’s time for a “curtain piece.”

Many greetings,

Pieter

War in Words 3: Dialogue with Vlatka Horvat

In 2014, Kaaitheater in Brussels ran a season titled Up In Arms, which featured a range of projects by artists responding to questions of international conflict and the legacy of World War One. They invited me to do a series of dialogues or correspondences with artists involved in the season, the results of which were published in Kaai’s quarterly bulletins. I’m posting those dialogues here in the Notebook, just to give them a different profile. The third correspondence, below, is with the visual artist Vlatka Horvat, the others are with Lara Pawson, Pieter De Beuysser and Pieter Van den Bosch.

Image above: Vlatka Horvat from her Up In Arms series

***

TE: The performance project you made recently drew on historical events surrounding the dissolution of Yugoslavia. What do you remember about the 14th Extraordinary Congress that your work refers to and why did you want to think back to it?

VH: The 14th Extraordinary Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, held in Belgrade in January 1990, was the last congress of the delegations of the Communist parties of all the Yugoslav republics. It was called ‘extraordinary’ because it was held outside the regular schedule, and on the agenda were questions of the country’s organization, structure, and decision-making procedures. The 14th Congress is significant because the Slovenian and Croatian delegations walked out after 2 days of meetings, after all the proposals of the Slovenian party – one of which was to restructure the country as a confederation – had been systematically voted down by the Milosevic-led voting majority. I was a teenager then, but I remember vividly being glued to the TV with my family watching the proceedings unfold in real time. There was a huge sense of uncertainty and trepidation in the room, a hovering question of ‘What does this mean?’ and ‘What’s going to happen?’

TE: Did it seem like war was inevitable after that?

VH: No, I don’t think so, not then. I left the country a year and a half later, in the summer of 1991, to go on a student exchange programme in the US, and at that point the wars hadn’t started. I think there was still some sense – or hope perhaps – that things could be worked out somehow, though I remember this line that was repeated often: “This isn’t good”. For months and months it’s all anyone talked out. But somehow every time there was any kind of escalation, people still held onto this belief that peace would hold. At least people I knew! Even when, for example, the war was in full swing in Croatia, people in Bosnia were still saying, “It couldn’t happen here”.

TE: That claim also came up in my dialogue with Lara Pawson, who underlined that in England there’s a common idea that we have some supposed intrinsic stability, the identity narrative that we’re ‘civilized’. The possibility of anarchy or breakdown far away is explained implicitly in the media here by the fact that other cultures supposedly lack the qualities that hold our society together. It’s a racist myth basically through which, the former colonial powers look upon other countries as somehow being predisposed to chaos and violence.

VH: Well the Balkans certainly share that kind of reputation! “The region”- as it’s now referred to – is often painted as the epitome of lawlessness and unruly instability in Europe. In response to what you were saying though I think one of the things my project is interested in is the strange set of shifts in perception caused by time. Looking back on that period now, certain escalations seem like they were inevitable because of the particular combination of circumstances and forces that were in operation at that time. But back in the ‘90s, I don’t think it seemed like that – at least not to my teenage self trying to make sense of the situation… It’s as if the narratives of looking back have a tendency to solidify things in some way – perhaps because there are vested interests at play in that process. Of course in other ways the passage of time can make things seem looser or more uncertain, as events are processed through different kinds of distorting lenses – lens of forgetting and misremembering, for example. They are as well as always contingent on the context of ‘now’ and – to a degree at least –affected by the various ‘official’ manipulations of information and of history.

TE: So that Congress is a trembling of the structure that is Yugoslavia and it’s the last time that the Communist Parties of the different republics meet. Can you talk about your 15th Extraordinary Congress project – about how it looks back at the end of Yugoslavia and at the war?

VH: 15th Extraordinary Congress was first presented during LIFT Festival in London in 2014 and this year I’m making new versions for Brussels, Berlin, and Bergen. The project assembles a group of six or seven women, all of them artists of one kind of another, all born some time in the ‘70s in different parts of what was then Yugoslavia and all now based in the cities or regions where the piece is being presented.

In the piece the participants spend 4 hours – working in a game-like structure of questions and time limits – reflecting on, or trying to answer the question, ‘What happened there?’ I like this question because of the different possible approaches and readings it opens up. It refers to specific instances of ‘what happened’ in terms of the break up of the country, but also ‘what happened there’ in other micro and macro arenas of life – in everyday life, in political life, in the media sphere, and so on. So the piece is a gathering that puts on the table a set of fragmentary answers, accounts, theories and positions, all of which sit side by side, decidedly unresolved, with all their inconsistencies and contradictions.

TE: Your 15th Congress, is all women, and it’s an act of looking back – after something.

VH: Yes, women don’t often tend to be the ones in charge of the “official” historiographies! All the participants I invite are also artists, who, like me, at some point and for a variety of reasons, left the country – a place in which we all shared some part of our lives, and this shared experience ended in 1991.

In one sense, the piece looks back at this place – ‘after EVERYTHING’ – which of course is a paradoxical thing to say, as ‘after’ is never definitive and never finished. There are always multiple ‘afters’ that follow. The piece deals with a lot of ‘after’ – after the First World War, after the Second World War, after Yugoslavia, after socialism, after that chunk of history we all shared, after the wars in the ‘90s, after the political upheavals that followed – which defined, in a lot of problematic ways, the relationships between the new countries there, and which are still, continually, being worked out and re-defined. And at the same time it’s after personal moments in the performers’ lives – it’s after we all left the place and are looking at it now not only from a temporal, but also a geographical distance. There is of course also a different kind of distance that accompanies those experiences and narratives of displacement and repositioning…

I’m thinking of yet another ‘after’ too – it’s almost as though 15th Extraordinary Congress takes place after you’ve stopped looking at ‘that place,’ after it’s all ‘over’ and you’re ‘done with all that’. I’m interested in that question of how do you look at a thing or at a place or at a period of time, after you’ve stopped looking at it, and also after it’s ceased to be the focus or the drama of the various ‘big eyes’ looking at it from the outside.

TE: It’s interesting to think about the rhythm of the international, geopolitical gaze, because there was that moment when the former Yugoslavia was high on a lot of people’s radar –

VH: Yes, it was the flavour of the month for awhile there! Then attention moved elsewhere – to the Middle East, to the former Russian republics, to China…

TE: Yes. The gaze follows unrest and volatile political situations, I suppose. It follows violence. It follows war. But what’s interesting of course is that after that particular media-led gaze has moved on; the people of any particular region, in this case former Yugoslavia, are still there, still dealing with their questions and their lives.

VH: Certainly – I’m very aware that anything I say is coming from a perspective of distance, perspective of ‘not being there’, and not having to deal with a lot of things – on the level of everyday life at least. The process of ‘looking back’ is always contingent on your current situation, and it’s very different if you are living the consequences and the aftermaths of all these things in tangible ways – on the ground, as it were. There’s also I think a difference in one’s willingness to look back when you are not there – there are different consequences to those processes; the ‘looking back’ affects your life differently perhaps. I’m also aware that my own removal, and my, now more-than-twenty-year-long, absence means there are also gaps in my understanding of ‘what happened’ and what is happening now. And I’m interested in those gaps – in what you fill them with.

TE: One of the things that struck me in your project is that it’s hard to list all the wars that it’s after – do you feel as though you’re dealing specifically with the ‘90s and after or does your conversation include that bigger sweep of history?

VH: My initial thinking about the project was framed as a response to the centenary of the outbreak of WWI. It was in the aftermath of the First World War that Yugoslavia was created, at least one of its versions (Yugoslavia had a lot of versions in its relatively short existence as a country). It was of course redefined very radically in the aftermath of the Second World War, when the version of the country that I grew up in was created. And then that version was dismantled in the wars in the ‘90s. I became interested in the idea of looking at a country as an object; this ‘thing’ that was Yugoslavia, which had a lifespan of some 70 years… You can pinpoint to the moment it starts and to the moment it ends – it’s a geopolitical object framed on both ends of its objecthood with wars. And – as in a lot of my work with objects, images and spaces – I’m always particularly interested in the dissolution of objects, the gestures and processes of their being taken apart, or their falling apart. And, in case of country-as-object, I wanted to ask how might you read that particular dissolution? How can you try understand it?

TE: How much is this a project in which you’re making a space for yourself and other people to encounter different sides of what happened? Were there things that challenged your assumptions about what happened in the build up to the wars and their aftermath?

VH: For each version I try to find participants born in different parts of Yugoslavia, but I don’t want to follow a ‘one person from each republic’ formula because I don’t think any of us is really keen to be framed in those terms, or to ‘represent’ a place in that way – I certainly wouldn’t want to. Plus, in Yugoslavia there were so many interweavings of social and cultural and national identities and sense of belonging that you can’t really do that kind of representation without perpetrating another violence.

While the piece is certainly interested in the inconsistencies and complexities of stories you might tell about a place, I was quite conscious that the participants in London were not so far away from each other in terms of our political leanings (and I’m probably making a lot of assumptions when I saw this!). But I think it stands that people further away on the spectrum might well have thrown up more radical clashes of positions and interpretations of history… Nonetheless, I was struck and surprised by the different frames of reading and understanding we each had.

As I said earlier, I think our understandings of what happened is to some degree affected by the rhetoric and discourse of the dominant powers in which each of us grew up. Even if you put yourself in opposition to those frameworks, people’s narratives still bear traces of, or clearly position themselves in relation to, whatever the official historiography or version or analysis of the situation is. So you are inevitably dealing with that picture, or those versions of the story also.

And of course different people’s personal experiences – what specifically happened to them, what happened to their families, what happened to friends or people around them – is very particular.

TE: What is it about this project and its desire to look back, your desire to look back – what’s in that excavation in relation to Yugoslavia and the wars?

VH: In a way it’s an attempt to understand the now, or to understand the possibilities of the future in some way.

I should say that for me this ‘looking back’ often has troubling aspects. It is often used to glorify a particular version of history, to construct the kinds of narratives that will serve those in power at any particular moment. There have been so many revisions of history in “the region” and how you understand or frame ‘what happened there’ is still very much up for grabs. Throughout history of this ‘thing that was Yugoslavia’ and throughout history of the countries that are there now, there have been several extensive rewritings, as though with every change of government, history is always being reframed, re-imagined, or re-invented. So I think the acts of looking back always beg the question, “What is the agenda of the looking back?”

But with all that looking back, there’s been a huge emphasis in the discourse of the dominant power structures on the opposite discourse too – that of going forwards. And in that rhetoric of ‘moving on’ and ‘going forwards’ there’s a real pull towards forgetting, towards erasure. So there have been endless revisions of the past through state interventions in public space and social space (enacted through the gestures of renaming, for example, of streets and institutions), through changes to which figures are supposed to be considered heroic, or changes to what ideas and principles should be regarded as ‘worthy’ and which ‘problematic’. Everything can get rewritten and rewritten again.

TE: I’m thinking about this crude narrative that goes from the war, and the nationalism that goes with the war, to the rise of the right in so many of those countries post-war, and the dissolution of socialism and the arrival of the rather brutal version of capitalism you have there now. Through that process, a whole culture gets swept out –Yugoslavia, the culture your parents invested their lives in as working people, the culture you grew up in. I’m wondering if for you the war, which is the way that Yugoslavia dissolves, is linked inextricably to the movements that follow it – the move to the right, and then into this very brutal free market – is that a single story for you?

VH: I tend to think of socialism and Yugoslavia as one period and from the ‘90s on as a kind of more chopped up period! There’s been a succession of governments since then, with a pendulum swing from the right to the former Communists to right again, ending up with some form of Neoliberalism – or whatever this is that’s in place now! I think the most dangerous, devastating thing happened in the ‘90s, with HDZ in Croatia and Milosevic in Serbia. Those ultra-nationalist governments thrived on a very restricted sense of national identity, subsuming culture for their political ends. With nationalist governments of course everything becomes a mechanism for creating sentiment and a sense of belonging, and anything that doesn’t conform to that gets framed as anti-nation. There is a way of conflating the perception of the government with the broader construct of the nation – this is not unique or unusual of course. In relation to that discourse, it becomes ‘problematic’ to be critical of the government because doing that frames you as being against the nation. I’m talking about the ‘90s mainly – which were bad times! But it’s worse now in many different ways. There is a version of capitalism there that’s unencumbered by any morality, marked with a complete erosion of workers’ rights, huge corruption, complete demise of the law and the justice system, and ‘each man for himself’ mentality. And all coupled with the extremely invasive and pervasive dominance and meddling of the church, in all aspects of public life. You put all those things together and it’s a very bleak story.

War in Words 4: Dialogue with Pieter Van den Bosch

In 2014, Kaaitheater in Brussels ran a season titled Up In Arms, which featured a range of projects by artists responding to questions of international conflict and the legacy of World War One. They invited me to do a series of dialogues or correspondences with artists involved in the season, the results of which were published in Kaai’s quarterly bulletins. I’m posting those dialogues here in the Notebook, just to give them a different profile. The last correspondence, below, is with the artist and performance maker Pieter Van den Bosch, the others are with Lara Pawson, Vlatka Horvat and Pieter De Beuysser.

Image above: Vlatka Horvat from her Up In Arms series

***

Dear Pieter,

Most of the artists in the Up In Arms season that I’ve spoken to, or corresponded with for these dialogues, have been dealing, to one extent or another with narrative – with the way that narration, and spoken language might help us process violence and conflict, and with the way that narratives (or information) about conflict might either help define or control us, or help (in some small way perhaps) to free us from different kinds of mythology, and political constraint in relation to our understanding of war. Your work seems to take another approach – something more direct and experiential, something closer to the ground, in terms of materials and actions. I’ve been looking at the videos of your work and I’m struck by two things – first by this focus on substances and physical processes, and second by the way that, in your work, you’ve been exploring ways of giving people direct experiences with, or close to things like fire, explosion and so on. What interests me about this immediately is the directness, and the lack of recourse to narration. What are you thinking about in making these works?

The second thing I wanted to ask about right away was the title “Attacks Without Consequences”. It’s a fantastically arresting and confronting title – I think because it so boldly states something that at first sight appears to be an impossibility. An attack, we might think, always has consequences. An attack is linked to the desire to intervene on another subject or territory, physically or intellectually, and it’s linked, in my mind at least, to the desire to cause harm. In what sense are you thinking about “attacks without consequences”? Do you mean “ineffective attacks”?

In the international political sphere – the only place I’ve really heard this phrase before – this idea of “attacks without consequence” seems to get wheeled out in Israel’s statements about Hezbollah, for example, where Israel’s right to retaliate (to cause consequences) to rocket attacks, is asserted. Does your work concern itself with this question of retaliation? I suppose what I find most interesting about the title, in fact, is that it opens this question about what consequence is – attacks have consequence on the victims, but to my mind they also have consequences on the perpetrators – violence is brutalising on both sides. Your work also opens the question for me about what is an attack, and who decides or defines that? States, for example, or political systems, perpetrate violence but it’s not seen as ‘attack’, more as the way things are! It’s more often those that challenge the state who’re called the attackers. A lot of questions there, I realise – but perhaps you could think a little around questions of attack and consequence – in terms of the work, and in terms of the wider world it reflects on?

All the best – Tim

*

Dear Tim,

Your question, “What was I thinking about making this works”, reminds me in first instance of a father giving his son a lecture about “not doing stupid things”. In many cases, and especially in my case, the answers could be: “I dont know, I wanted to see what would happen”.

I do know that all my actions are aiming for one purpose: showing a moment of transition. I’m interested in that, because during those moments the old and new rules of a situation are not fixed. For me the most imported or drastic changes happen in moments we don’t control or understand and we are mainly busy with the consequences or preparation for or around them. Gathering more knowledge and skills in the unknown gives the possibility for evolution of the present context or situation. Therefore I use and chose materials that have a autonomous manifestation potential and that cause a strong reaction. The reaction I’m mainly interested in is the movement towards or away from the situation. If we are scared we run, if we are reassured we approach, and when we don’t know… then what? In fact I need people to make the manifestation of the material clear. In the end the work is more about the material than about people.

Attacks without consequences

I think that an attack, in general, tries to destroy. An attack ‘without consequences’ holds in its title a human perception that the attack has missed its impact and stays without bodily or material damage.

I believe that only the attempt of the attack exists, and that there are always consequences. Take for instance a lion, that can catch an impala after 7 attempts. Only the 7th attempt has definite consequences for both animals. The 6 attempts before are part of the attack and are learning experiences in how to adapt in order to survive. After the 7th time the attempts stop because the goal is reached.

I feel very limited in discourses about big conflicts in the world. I have an opinion about it that is always overshadowed by an awareness of my own European perspective and limited and incomplete knowledge about these conflicts. What I know for sure, is that we are exposed daily to a great number of images, of things like explosions, fire, casualties, destruction, that for us form the image of ‘war’. I protest against that because these images are showing the materials I work with daily in a very negative and one-sided way. In first instance the attacks without consequence for me are fire constructions more than attacks, in order to give more space and freedom to the manifestation of the material itself.

Do the experiment, make a part, put a candle on the table, keep some water nearby, knock over the candle and see what happens. But please don’t do stupid things.

all the best

Pieter

*

Hi Pieter