Back at HKW in Berlin last month during the same programme as Vlatka‘s This Here And That There, I got chance to see Julie Tolentino’s great performance A True Story About Two People. In it Julie (who’s worked frequently with Ron Athey) dances barefoot and blindfolded for 24 hours continuously on a square of grass, inside a small mirrored booth. Strange that so simple piece as this one can multiply complexity in all directions as soon as you look at it, but I guess so much of my favourite work in performance (or in art more generally) is like this; clear, consequential, following a logic and irrefutable on the one hand and layered, rich, and (basically) bewildering on the other. Those two states, those two facts, sat side by side/on top of each other/overlaid at all times. Yes/And.

Visitors to the gallery are invited (by cards on a table next to her booth) to join Julie on the square of grass and dance with her, one at a time. If there are no takers she dances alone, whilst at other times there’s almost a queue, and very often there’s a small crowd of onlookers. This process goes on for 24 hours, a melancholy dance marathon for a single contestant with a constantly shifting (and sometimes absent) dance-partner. Throughout the work, music – country and western, ballads, torch songs, all sorts – slips from the speakers in the booth itself, the songs gliding in and out of each other, mixed to a landscape with the sound of crickets whose chirping adds its weight to the modest suggestion of the grass – that we might think for a moment of outside, of night, and of some other place than here.

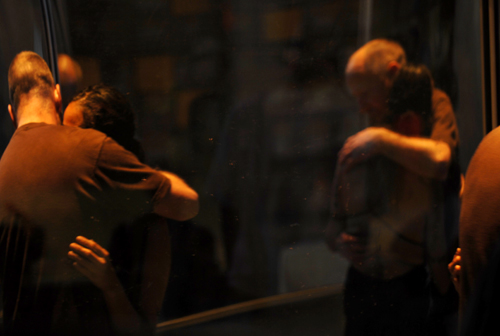

Viewed from the outside the mirror panels of the booth let you see into it, though what you see is shot through, from time to time and depending on your angle of view, with reflections of the gallery, yourself, and passersby. Step into the booth through its open side, to dance though and the scene is very different. From within, as you’re dancing, the three screens are perfect mirrors, thanks to which you don’t see outside anymore. There are no more other people – only yourself, and her together, distorted, reflected and re-reflected – the two people of the title (now you and her, no longer her and a stranger) are doubled or multiplied out from your bodies as a series of moving images, phantoms, wraiths, memories, optical illusions. You feel, smell, touch, see her, but at the same time glimpse this shifting three-sided horizon of your dancing versions.

Seen after 12 hours of this work Tolentino cuts a frail figure in the booth, moving vulnerably, softly, made something of an object by her sightlessness. Reversing this impression though she retains both a strength and a privacy, like she’s able to deal, content in the fact that she’s alone and unknowable – a blank resilient figure. Hard to be sure if she is the victim of the economy she has set up (or mirrored) or if she is its master, hard to know if she serves this machine of encounter or if it serves her in some way. One’s sense of what levels of compulsion, work, need, desire, banality, sadness or joy govern the transactions that take place here is something that’s constantly shifting. Yes/And.

There’s been a fair amount of ‘for an audience of one’ work in performance in recent years and I’ve often had my doubts about it as a mode; it can seem like just too handy a short-cut to intimacy and affect, a route in which the formal decision too-often outweighs or doesn’t even speak to the content. Here though, in Julie’s work, as in Franko B‘s unforgettable Aktion 398, the formal decision and the content are the same thing, completely indivisible. It is what it is; a frame, a space in which a meeting takes place, an opening to possibility and to another person. And I guess A True Story About Two People isn’t ‘for one’, or isn’t really about two people in any case – its about the construction of two, its impossibility, its resonance and its possibility as an act in social space. As I write to a friend shortly afterwards:

“Intimate and totally public, contact but no contact at all, a meeting of some kind, but one that takes place basically inside your own head.. And the whole of the time in there is an occasion for a conversation with yourself of course, about this space of encounter, about holding and moving with another person… About watching and being watched, about what is and what is not.

Perhaps the strongest part of the piece is/was the moment of leaving her. When to leave? After a few songs, after a period of time? At least after the time when it feels like ‘something’ happened or something was exchanged. It can never be the right moment of course. I think I waited for the end of a song. What felt strong was that I looked for here eyes – to negotiate the departure – and then of course realised that, thanks to the blindfold – her eyes were not there. So I had to say goodbye by means of slowly letting go my touch.”

Watched from the outside some visitors seem to talk a lot. Others not so much. From the look of it they ask lot of why’s, how long’s and how are you’s. I’m guessing. But it looks like the small small negotiations of the ‘being there’. Physically one can see that there are the questions of what to do with the hands, how close to be, of where to go with the feet. The problem of tall persons (she is short). The problem of people that are too enthused (she is tired). Some are smiling. Some serious. Some easy. Some almost rigid. As for the movement itself; some dance with a little comedy in their step, some with moves in grinning quote marks. Or a raised eyebrow, that sends the eyes out to those watching outside, as if to say “Oh, yes, look at me. I am doing this. Dancing with her, here, in this place now…”

All those ways of engaging with the piece are possible, and a part of it of course. But they’re also a kind of avoidance, a way somehow not to be there. The piece, at its heart, wants to draw you into a space of intimate proximity with another human being – based on dancing, touch and movement – and asks simply (in full complexity) that you spend time there. Both times I took off my shoes and went in to dance with Julie I talked with her at first as we danced – the how’s it going, the this and that. The second time in, I even told her a story I’d remembered as we’d danced before, something from an old performance, a love story. But then I shut up, which for me at least was a kind of surrendering to the being there, to the thing of it. It was only then, in a certain way, that the piece started in earnest. You dance, move, hold. Hugo Glendinning took the pictures above and many others, without my even noticing. You think, drift, watch the mirrors, maybe close your eyes. You wonder – about her and how it is, about you and what this is, this contact. You think – about other dances you did here or there, or other dances you did not do here or there. Its a small space that you’re moving in (literally and as metaphor), but it goes down deep. It can be sad, ordinary, delightful, tender, awkward. Shifts in between all these things, tries to find what it is, this meeting between you and her, surrounded by ghosts/reflections. It’s an economy of taking and giving – that you give something to her by dancing, and that you take something too, the balance uncertain, in constant negotiation.

The goodbye is the marker moment, as I wrote already. Because then you have to deal with the fact that she’s not ever in it on the same terms as you were, that she’s locked in it in fact, since whilst you can leave she’s in it for good – a production line of sorts, in which many others like you come and go, to look, hold her, talk, dance, and leave and that she alone stays, dances, continues – trapped in one sense and way stronger than you in another. Yes/And.