Some video of my sound piece Stand Off, in situ in my For Now solo exhibition at Plymouth Arts Centre. Runs until January 3, 2016.

A Task Become A Theatre – Intro to Deborah Pearson’s The Future Show

Sharing Battersea Arts Centre this week with one of the most interesting performance-makers in London right now, Deborah Pearson, who plays a double bill of performances Time Pieces, comprising her solos Like You Were Before and The Future Show. The performances are at 7.15pm and 9pm and run until 7 Nov. Through the same week and into the next Forced Entertainment plays The Notebook, which runs 3 to 14 Nov, I’m also presenting my solo A Broadcast / Looping Pieces on Saturdays 7 and 14 Nov at 5pm.

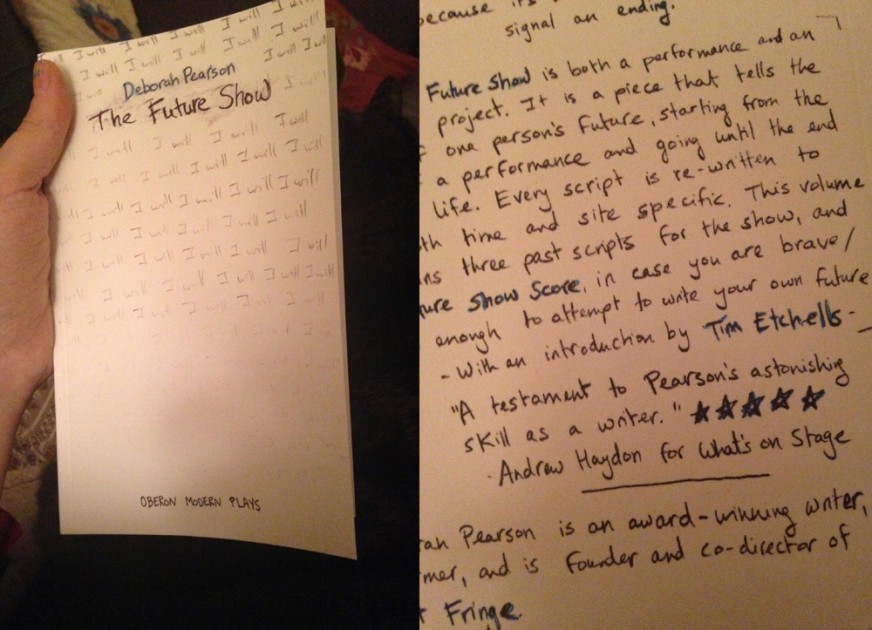

I saw Deborah’s Future Show a couple of times now, once as part of the Irregular Evenings series Vlatka Horvat and I were curating in London, and later in this years’ Malta Festival Poznan which I co-curated. It’s a really great piece. In a timely fashion Oberon Books are just publishing a book of The Future Show, containing three versions of the text for the piece, which is rewritten for every presentation, along with Deborah’s extended notes on how to make your own version of the work. Deborah asked me to write the intro for the book, which we agreed I’d share here – it was a pleasure to engage with the work in some detail. You can order a copy of the book at Oberon’s site – it’s recommended.

***

A task become a theatre

It’s all there at the start. The woman at the table, the folder of A4 pages, the glass of water, the act of reading (a task, which here becomes a theatre).

In fact she starts already teetering, stepping off the edge of the moment she occupies and into the future, boldly in the first sentence already stepping to the end of the performance, to the closing of the book and the ocular cancellation of the text she is reading from, by that time completed, and in that same moment stepping to the ocular cancellation of your vision, the dimming of the lights, and stepping also to your predicted applause; the acoustic cancellation of the spell of her voice. She steps forwards into the future and keeps walking, ahead of us, reporting the future as if over-her-shoulder but in fact speaking directly to us, reporting what will come in good part as a set of non-negotiable facts, immanent facts, facts-to-be, of which her present self, whilst calling them back to us, makes little (or is it absolutely no) judgment, comment or assessment.

“And I will say…”

And in the next hour or so she will race ahead of us thus, talking up time, taking time and making it, making years of our minutes, soft, precise, pedantic in the detail of her conceptual life, its scenes and stages, its ups and downs through and in the jittering flow of which, she is slowly and softly painting herself into a corner.

It’s all there at the start. After the holiday, after the PHD is done, after the brief fling, after the shopping trip, the travel for work, after some moment of reflection, after this or that, the growing older, the love, the family, the work, after all of that, of course, she will reach that corner and die. It’s inexorable. She will die. Tonight. And again tomorrow, and, if business is good and the audience up for it, she will die again the night after, progressively more tangled in her own story versions and entrails, but always dying, always the same.

The presence of the book on the table, the accumulating versions of her future, three of which are included here, is testimony to the core status of the piece as language game. You feel a bit of Georges Perec here – with his endless descriptions of the same view from the same café windows, or his words wreathing always the same banal objects, as if by returning his gaze to these scenes and items repeatedly they might yield their truth, their real story. Perhaps Pearson takes this approach to her future – looking and looking again; refining it, working it down and around, mapping the flux of the possible towards the singularity that she will inevitably be, the her that is closing slowly around her.

But Perec’s endless return to the everyday makes no claims to reach for the unknown; it’s avowedly an act of looking, an insistence on what is – in equal parts tedious and joyous, finding the unseen rather than the unknown. Pearson’s text meanwhile steps away and out from the already evident, searching her own present, her own sense of herself, the narrative of her own life, for the seeds, signs and fissures that already lead, point and open to her future. Everything now, everything present, is only fuel to her future; the lobby of the theatre, the staff at the hotel reception, the taxi driver, the friend in the hotel, the clouds above the city here become openings we watch her push at gently, as she steps out future-wards. We watch her go.

“And I will take the District Line..”

Watching Pearson I have to think a little of the protagonist of Russell Hoban’s Pilgerman (1984), whose Young Death is following him through the novel, gaining shape and clarity with the passing of the years, getting clearer, sharper, better defined. Or of the Herman Hesse novel The Glass Bead Game (1943) in which acolytes or students of the game undertake to write three versions of their lives (and deaths). I’m thinking too of the performance I made with Forced Entertainment The World In Pictures (2006) which ends with performer Jerry Killick’s accelerated imagining of the audience as they leave the theatre, through the days and weeks in which they do or don’t remember what they have seen, leapfrogging years through the rest of their lives to their eventual deaths, to the deaths of all that know them, to the transformation and forgetting of languages, to the change, decay and then destruction of the city outside, to the end of human civilization, to the eventual erasure of the world, the place of the earth left vacant as only a vacuum in space. I’m thinking also of visual artist Beth Campbell’s My Potential Future Based on Present Circumstances (1999 – present) in which she has, over the course of many years made a series of diagrams and drawings in which her options, potentials and possibilities, play out in gardens of forking paths, flow charts that map her successes, relationships, depressions, discoveries, failures and forthcoming life-choices as a network of either/or’s, played through to multiple conclusions.

But Pearson’s work is its own universe, a methodical conceptual writing-project undertaken over a period of years, whose reflexive task involving the adjustment and ornamentation of sentences, paragraphs, linguistic images and futures is also a kind of magic act, a conjuring and transgression of quotidian time. Gentle though the piece is, undramatic even, its dynamic heart is meshed with deep cultural taboos concerning prediction, and the fearful properties frequently ascribed to the actions of speaking and writing when they address themselves to the future.

To write your future, to speak it, to name it, is an act invariably shrouded with unease. The act of prediction, of seeking knowledge ahead of time, of articulating or claiming knowledge in advance of events puts the subject above or outside the constraints in which humans are usually expected or burdened to operate. Premonition, prediction or pre-knowledge is a rupture in the temporal order, a reach for power, a transgression; an unseemly land-grab from the gods, fate, free-will or the random machinery of the universe depending on your worldview. “I will.. and then I will..” is a form of impossible knowledge, as forbidden as it might be desirable. The act of reading on which Pearson embarks, from the outset of her piece, however simple in its means, unassuming in its performance or cool in its conception and execution, is non-the-less a violent magical transgression, a breach in the quotidian universe.

Those who author or are party to such breaches in the temporal banal, demanding, claiming or proclaiming impossible knowledge, are doubly trapped by their actions – the future they name may come to pass (the past utterance become a future prison), or, on the other hand, the future as named may not come to pass, its path failing, swerving, changing or mutating in new directions, reacting to the predictive utterance, avoiding it, or obeying but at the same time thwarting it. Narrative, for the most part, is far from kind to those who know, claim to know or seek to know the future.

The loosely programmatic nature of Pearson’s project – moving forwards day by day, through weeks, months, years of her life – is a simple but audacious piece of temporal trouble-making and we feel the self-destructive charge (and burden) of it, quite regardless of any sort-term playfulness, poetry and self-invention that the piece typically supplies. We worry for her, knowing that she reveals (and will end) herself, suspecting (with however much irony) that the choices she makes for the ‘Deborah Pearson’ described on this particular night may have consequences for the Deborah Pearson who sits before us, down the line. She is (to put it bluntly) tempting fate, and whilst she is kind (or selective) to herself on the whole, ones concern is not so much that her alleged future will come true, but rather with the tangle of accumulating possible ironies, possible coincidences, possible twists and turns that she is making a ground for, up there on the stage, throwing her linguistic mirror-selves into the universe and watching them cloud, crowd, fail and fall around her.

She is kind to herself. Pearson’s predictions offer little or nothing in the way of drama or hyperbolic invention; no car crashes, no revolutions, no murders, no court cases, no hauntings, no divorces, no rapes, no debilitating or disfiguring illnesses, no grinding poverty, no war or social collapse – just a micro-managed continuous everyday of her life, her ongoing life, pretty much as lived at the point of her writing but continuing, changing. She takes her task playfully, seriously, with love, making a miniature, with all the care, attention to detail and engagement that might suggest. For all that the performance is a highly manipulative, affective architectural construct there is nothing brash or trash here. Instead you sense her taking care with the materials. She takes care of the life she is describing, lest the game of the piece collapse to the status of a mere word game, tending the construct of her futures-described as one might expect her to take care of her own future proper.

Her care takes other forms too. In the text she skirts her own death, at least in the sense that she never names it exactly as such. She plants children in her future but again, avoids the full on fate-tempting procedure of naming and numbering. Her work remains hazy. She appears vague as to the fate of her husband. Throughout there are details, fragments of future. But despite its apparent straightforwardness it remains somehow only the shape of a life, an outline, with clear views only at certain moments, hologram fragments which gently imply the larger scene, the unfolding passage of weeks, months and years. She goes forward.

“And I will reach up…”

There is a large sleight of hand of course, in Pearson’s presentation of The Future Show as a kind of experimental time-lapse theatrical selfie. She is, for the most part, busy telling us that it’s all about her, that this is yet more millennial self-obsessive diary stuff. But it’s not, not really, not like that.

The reality of this task become a theatre, is that it’s an act of reading in its other sense too; that of reading the future, each syllable of the performance functioning as a sign, oracle and prediction, her letters, marks on those printed pages in the binder on the table, as much tea-leaves as alphabet. And of course, the quick of it is that throughout she is speeding our time just as much as she is speeding her own, putting our lives on fast forward, creating a space in which we reflect on our own futures, possibilities, the landscape of our own what’s to come, all the time slowly and quickly taking us to our graves, en route to her own.

We too will die. There are no straight or easy deals when it comes to forbidden knowledge of the future – only crooked ones, only deals in which the client gets burned. Whilst as spectators here we never asked that our fortunes be told, we should have known very well that the mirror would turn, kindly at first, but then of course not so benign, that we’d meet our ends in following to hers.

Even before we see her end we are also moving to ours, stood since the very beginning on a precipice, our years talked out and away as seconds, our lives slipping past in the same hyper-speed, stop-motion as hers, locked together as we are, like objects falling in orbit of each other.

Enjoy. And take care.

Tim Etchells.